Paul Shaw’s essay on William Dwiggins’ work is a well-polished summary of the man’s work in advertising, book design, and typographic design. He lived from 1880 to 1956, but his philosophy steered away from many of the typical styles to spring up during his lifetime: Arts & Crafts, Art Nouveau, even Bauhaus. His designs were meant to be functional without appearing machine-like, and he used geometric ornamentation and peculiar colour combinations to punctuate the design. His type designs were meant for specific purposes, and he managed to keep a calligraphic quality to them despite their ultimate forms as metal type. He was above all an embracer of the machine, calling handcrafted works that imitated a machine’s job as phony (precursor to Catcher in the Rye, maybe?). Nonetheless, he was a Modernist, in the same sense that Louis Sullivan was a Modernist. While this comparison was never made in the text, I think that Louis Sullivan and William Dwiggins’ philosophy were closely related. They both revealed the structure and limitations of their product; Sullivan revealed the steel beams that supported his buildings as Dwiggins’ designs supported rather than subverted the content. They both abhorred mindless ornamentation or products lacking thereof; Sullivan’s ornaments were tiled and uniform throughout his buildings as Dwiggins’ ornaments were produced with a repetition of stencils that he reused throughout his works. They both believed in specifying every detail tocreate unity between the purpose, material, and design of the product. The essay’s rather astute observation on Dwiggins’ fade from general design knowledge struck a chord in me; I knew of his contemporaries, I knew his essays and typefaces, but I did not know him. I am thus grateful to have read the essay.

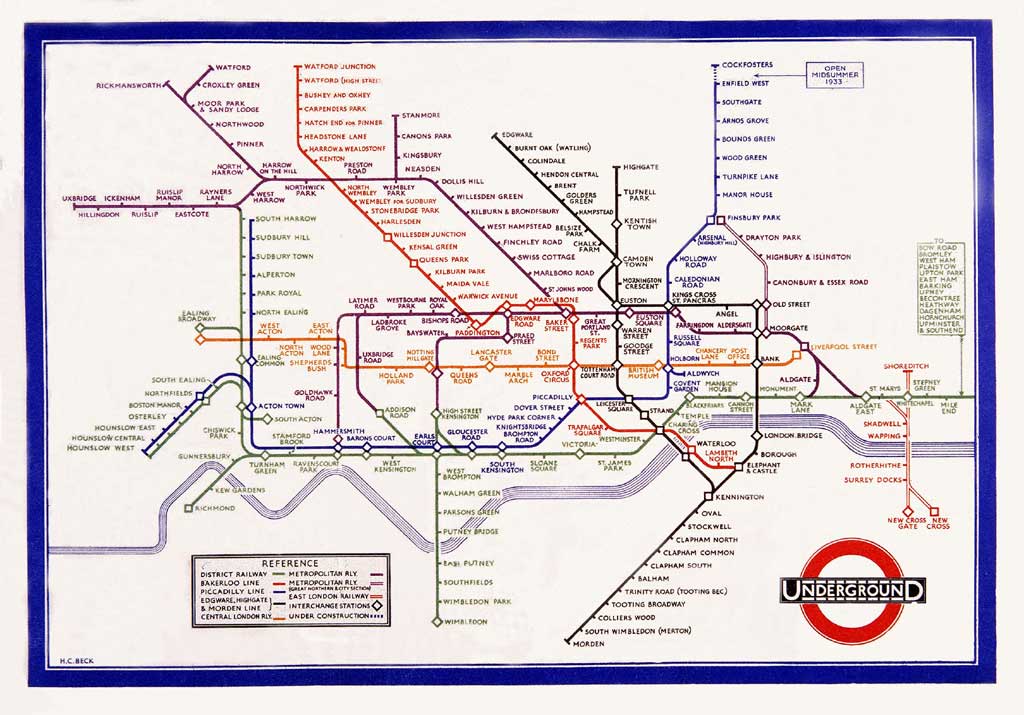

I found it difficult to situate Paul Elliman’s Signal Failure into the significance of modernism. The essay begins with a comparison of the London Underground’s map system, designed by Harry Beck, with an electrical circuitboard (which Elliman then noted that every essay/article ever written about London’s subway system contains that comparison). However, I found that Elliman’s writing was redundant and went nowhere. There was no insightful conclusion, and his passive aggressive tone of disapproval for the system’s machine-like qualities left me slightly confused and distanced from whatever point he was trying to make. The London Underground mirrors a circuitboard, and cities can at times resemble a machine, with people scurrying about like dutiful electrons in an electric flow, the end. It is easy to say that in the 1930s when modernism was already well-established, Beck’s map was able to integrate itself more seamlessly into culture than if it was released in, say, 1830, but honestly I think it was simply coincidence, and not some cultural shift of technological acceptance. Rebuttals are welcome from those who understood Elliman’s essay.

Ellen Lupton’s essay on Otto Neurath’s approach to an international visual communication (ie: isotypes) is an interesting read, though focusses, in my opinion, too much on Neurath, whose work ranged from the 1920s to 1940s, and not enough on the opposing arguments for visual communication. The idea that reducing objects to their silhouettes and creating a consistent style would pave the way for international communication is on par with Le Corbusier’s International Style, and about as sterile and chauvanistic. While I think the development of a consistent visual language to communicate facts is a necessary development in design aesthetic, is it still a necessity? We’ve now, to some measure, moved away from Modernist thought and have recognized this “international style” of Neurath’s to be an aesthetic that can be applied to many different manifestations of ideas and statistics. During my read I felt arguments against Neurath’s applical of logical positivism rise up instead my head, and was only partially satisfied with Lupton’s conclusion in outlining different perspectives on isotypes and visual communication. Is studying Neurath’s theory on isotypes is still so revelant to our understanding of visual communication that it deserves 12 pages of study compared to Lupton’s single-page devotion to opposing theories?

The line in Shaw's essay I liked best was a paraphrase from Dwiggins: "Better way -- to accept the conditions and materials and work out an aesthetic on that basis." For me, this pragmatic approach to working with the machine, as a tool, rather than resisting its presence and asserting the notion that handcrafted is superior, situates Dwiggins clearly as a modernist. It doesn;t appear that he minded the presence of "the machine" in his work. He was most concerned with discovering an aesthetic which was authentic (versus phony). Dwiggins is new to me but I am motivated to learn more!

ReplyDeleteWhen we look at older maps we usually see a pretty direct representation of a city. Something like this: [ http://www.historyofholland.com/_images/oldcitymapofmaastricht.jpg ] represents a scaled down version of this town, showing many details; roads, houses, rivers, etc.

ReplyDeleteTo "capture a modernist vision" a new way of mapping would have to completely disregard the past and it's realistic representation of the city and adopt something new and industrial.

I feel that the relation to circuit boards and the implication of city as machine has less to do with the modernization than the actual map itself. By showing no landmarks, no points of reference and no relational curves, I feel the map embodies modernism at that time.

I found a interesting article talking about New York's new underground maps in relation to London's, if you wanted to check it out. There are some good points brought up: [ http://www.thefreemanonline.org/headline/of-maps-and-modernism/# ] What caught my eye was the sentence: "Thank goodness it still doesn’t look anything like the map of London’s Underground."

Khuyen, I think that having a consistent visual language is a necessity more so now than when Neurath was developing it. With so many people travelling having certain standard signs for things like "phone," "washroom," "lodgings," "gas," and "stop" are incredibly useful when outside of your own verbal culture. One of my favourite isotypes is a relatively new one. The international breastfeeding one designed by Matt Daigle in 2006 in a competition by Mothering magazine. (http://www.breastfeedingsymbol.org/history/)

ReplyDeleteI agree with you that reading more about opposing theories would give a balanced viewpoint, but I found the article to be very engaging... maybe because I haven't been introduced to these ideas before.