The future, as illustrated by Disney in the Tomorrow Land and Epcot Center theme parks, along with most other mid to late century conceptions of a futuristic society, are entirely endebted to Norman Bel Geddes' vision. Originally a theatre set designer, Bel Geddes created a model for industrial exhibitons and fairs that dominated public relations strategies even decades later. He is best known for designing General Motors "Futurama" exhibit, which was first shown at the 1939 world fair in New York.

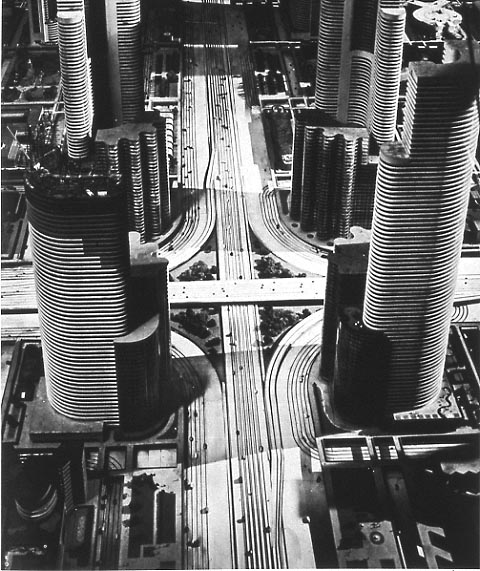

The exhibit was comprised of a sprawling scale model of a city in the not so distant future, with the emphasis being on increasing the speed and efficiency of the highway systems (required due to a projected increase of cars on the roads). The first half of the exhibit is a tour of the model from an aerial perspective, finishing with a life size replica of an intersection of the model, were viewers would be able to roam the walkways and enter the buildings (complete with gift shops) of "Tomorrow Land".

Bel Geddes was succesful in creating a massive buzz around the General Motors Company by essentially reinventing the image of the company. Prior to hiring Bel Geddes, GM was without any real concept for the exhibit, they had resigned to simply showing the viewer how automobiles were made (the status quo for inustrial exhibitions at the time). Bel Geddes' theatrical approach to involve the audience in the "show" while still mainting complete control proved to be very effective in masking the fact that GM had very little to say, and certainly nothing new.

The Futurama City was an idea Bel Geddes had employed (on a much smaller scale) for Shell Oil's "City of Tomorrow" ad campaign, which also dealt with the issue of overcrowded highways in the near future. While pitching his design to GM executives, he bluntly stated that they hadn't had a new idea in 5 years (Gm would continue to show the Futurama exhibit well into the 1960's). The exhibit succeeded in using optimistic propaganda to mask a a purely capitalist message; buy more GM cars. This is hidden, under a veil of concern for the well being and safety of motorists across the country, and an idyllic picture of an unattainable future.

Bel Geddes created a fantasy world that shared certain similarities with our understanding of retro today. Firstly, his future is without any substantial social, political, or cultural contexts to exist in. The model suggests that the highways will be easily navigated and very safe, allowing for people to live in the suburbs but still commute into the city for work with little discomfort (traffic, accidents, etc.). Aside from that, the exhibit is a grandiose shell of modernistic rhetoric aimed at appeasing consumers during the depression. Like retro images, the exhibit does little to address any projected circumstances of the time period (1960) in detail, instead focusing on developing a collective sense of optimism for future technological advancements. It also operates on a similar level of transparency and irony shared with the retro image. The exhibit is host to an audience during the tail end of a country wide depression and a war in Europe and the Pacific. In 1939, the future looked anything but bright, and the exhibit feeds on an instinctive desire for circumstances to improve into some untangeable utopia.

Reading this article and Nate's summary reminded me of the GM Pavillion at Expo 86 in Vancouver. The Pavillion was incredibly popular. Why? Wel, it had a hollogram of a native Canadian telling stories. As mentioned above, theatrical in nature. We, the audience, partiicpated by watching the hologram appear and disappear while story-telling. And, again, it distracted from a focus on cars and innovation. If you're curious, check it out: http://bobbea.com/expo-86/gm.html

ReplyDeleteI don't even remember the cars that were somewhere in the pavillion but the purpose, from a marketing perspective, I am certain was to create a strong association in the audience's mind of GM and special effects which is akin to saying GM is technologically advanced and saavy. Interestingly, the subject matter was very traditional and describing a low-tech object, a canoe. Again, a point of contrast to demonstrate progress but dressed up with a good dose of nostalgia.

Regardless of the year, it strikes me that GM's approach to these exhibitions is to create a pavillion design which develops its brand as an innovative, futuristic company. And, it wants the pavillion experience to engender awe.

I think the idea of 'Futurama' as well Expo 86 hearken back to the Crystal Palace of 1851. Countries from all around the world coming to Hyde Park in London to show off who was culturally advanced. I think it's interesting this thing we think of as old such as 'Futurama' or Expo86 turning out to have origins much older, yet to have so much in common.

ReplyDeleteWell done Nate.

ReplyDeleteGebbes and Disney must have hung out in a past life. They both loved to thrill people.

What was interesting about him was how he created a strong role of emotional engineering of people: how to feel, when/what to react, completely out of being a designer. His Futurama was planned right down to the molecule: from the whispering personal soft voice tone of the narrator and the lighting effects...to the experience ending making the Futurama experience a very real transition with reality.

As far as Alfred Sloan of GM was concerned, one way or another they were going to end up making more cars, and hence, more profits. If you promote the idea to make a bigger highway, you'll have to fill it up with more cars. Gebbes didn't directly sell cars, he made an impression on people that would indiectly focus them on GM when it came to purchase time.